Over the past few weeks I have been thinking a lot about the cultural differences between East and West and the very different value systems the two have come to live by.

I first started to think about this after reading Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s essay: In Praise of Shaddows (1933) a month or so ago. I found the book to be extremely moving and insightful. I was really interested in the affinity Tanizaki identified in Japanese (and more broadly Eastern aesthetics/ culture) towards darkness, emptyness, silence and ambiguity and the way this informed the way people lived. These qualities were in contrast to Western attitudes Tanizaki also identified or fullness, excess, and extreme clarity and perfection.

Watching an Art 21 episode on Bejing a bit later, I found myself returning to these ideas again, becoming interested in Chinese contemporary art and its place on an international scale. Looking at the artist mentioned in the episode, such as Song Dong, Yin Xiuzhen and Guan Xiao, I realised that their work operated under a different value system to that in the West. I was fascinated by the fact that my Western framework for understanding art was in many inept and perhaps wrong. This led me to realise the fact that our value systems are not universal.

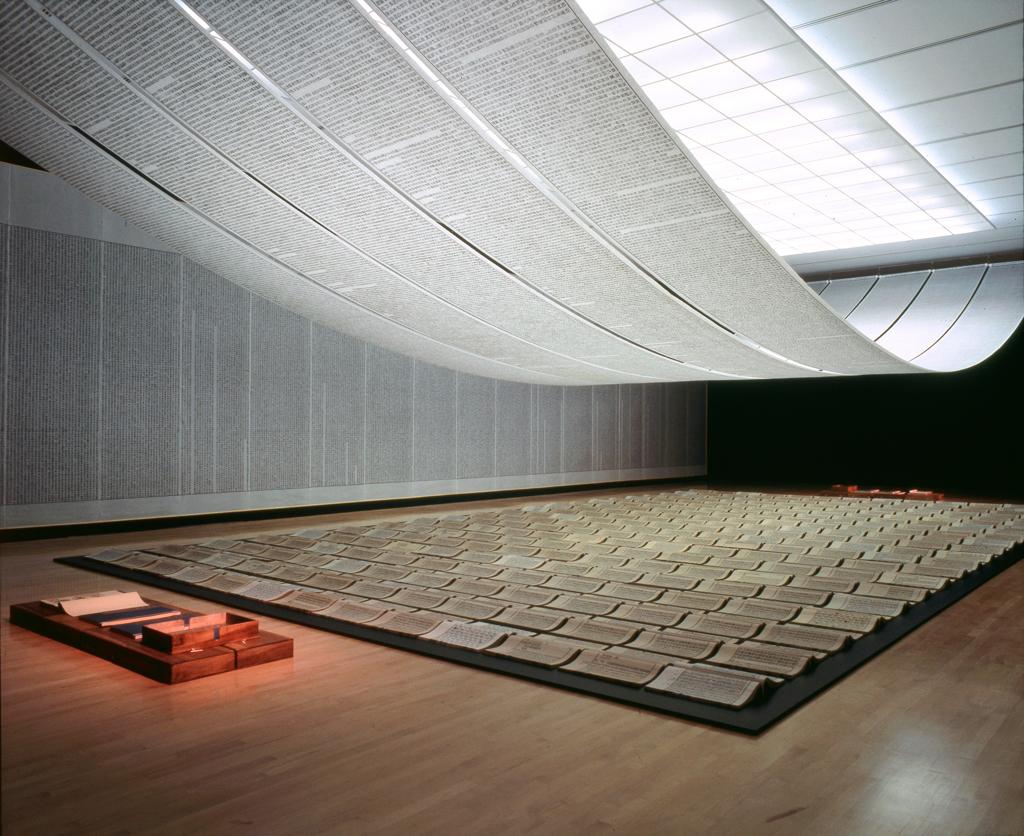

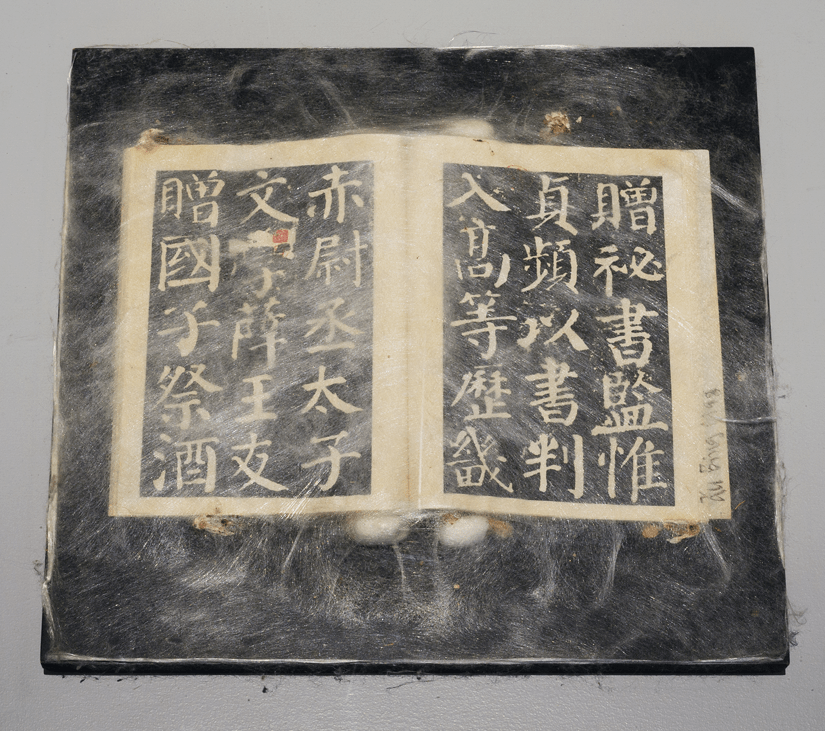

Out of all the artist I discovered in the Art 21 documentary, for me I felt there was no artist who better illustrated this than Xu Bing. His work plays with expectations, often presenting itself on a surface level as one thing only to be something very different inspected under closer scrutiny. His most famous example, which started his career as an internationally renowned artist, was his 1991 work Book From the Sky. Taking on the format of a revered ancient Chinese classic, upon first glance the work appeared plainly familiar to the Chinese population first encountering it. However, upon coming closer and trying to read the work, the viewers were denied any such meaning, finding the work consisted of thousands of meticulously crafted meaningless words which Xu Bing worked on over a period of four years. The characters resembled such a close similarity to real Chinese characters that many viewers when it was first shown did not believe it and searched hopelessly for meaning. Xu Bing shortly after left China to continue his work, further confusing the meaning of his work in relation to its new Western context.

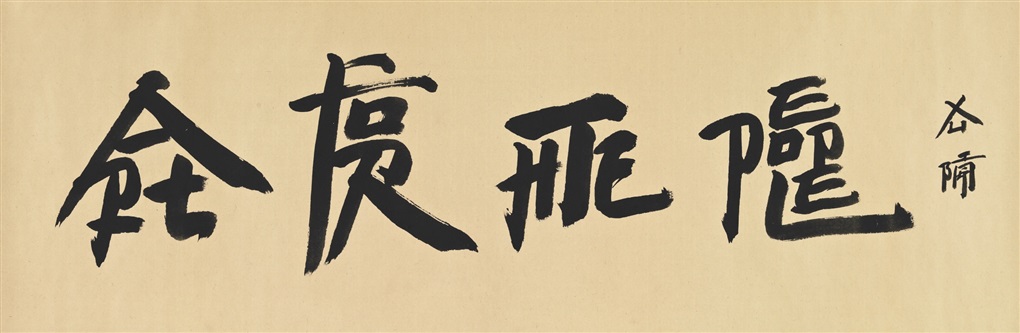

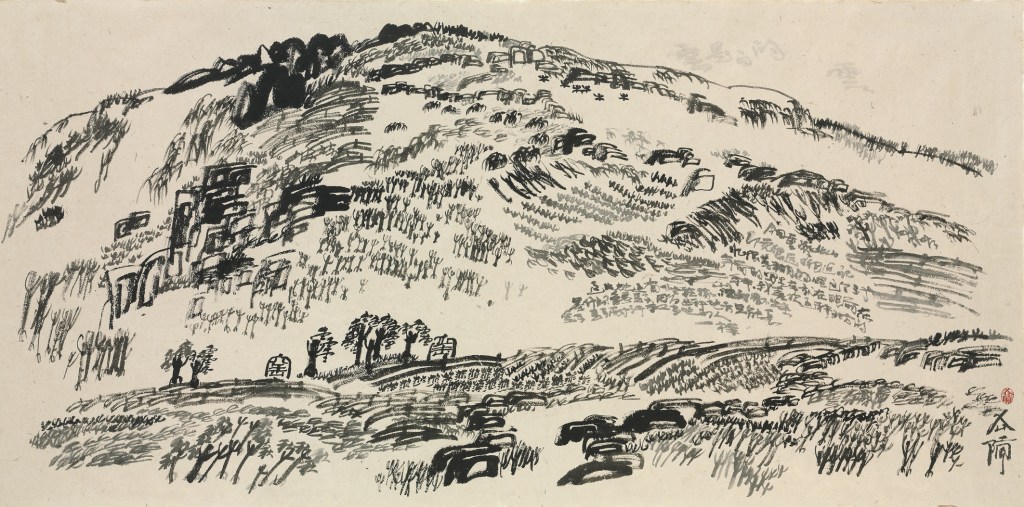

Most of his work since has followed a similar format, such as his famous ongoing Square Word Caligraphy project started in 1994 in which english words are written to look like Chinese characters (see title image: Art For The People), his Landscript series (1999 – ) in which landscapes are depicted with the words correlating to the things within them, or his Panda Zoo (1998) in which pigs were painted to look like Pandas and shown in a fake Chinese Garden.

His work continues to fascinate me and I am still trying to understand it in its entirety.